Meet MAGA’s Favorite Communist

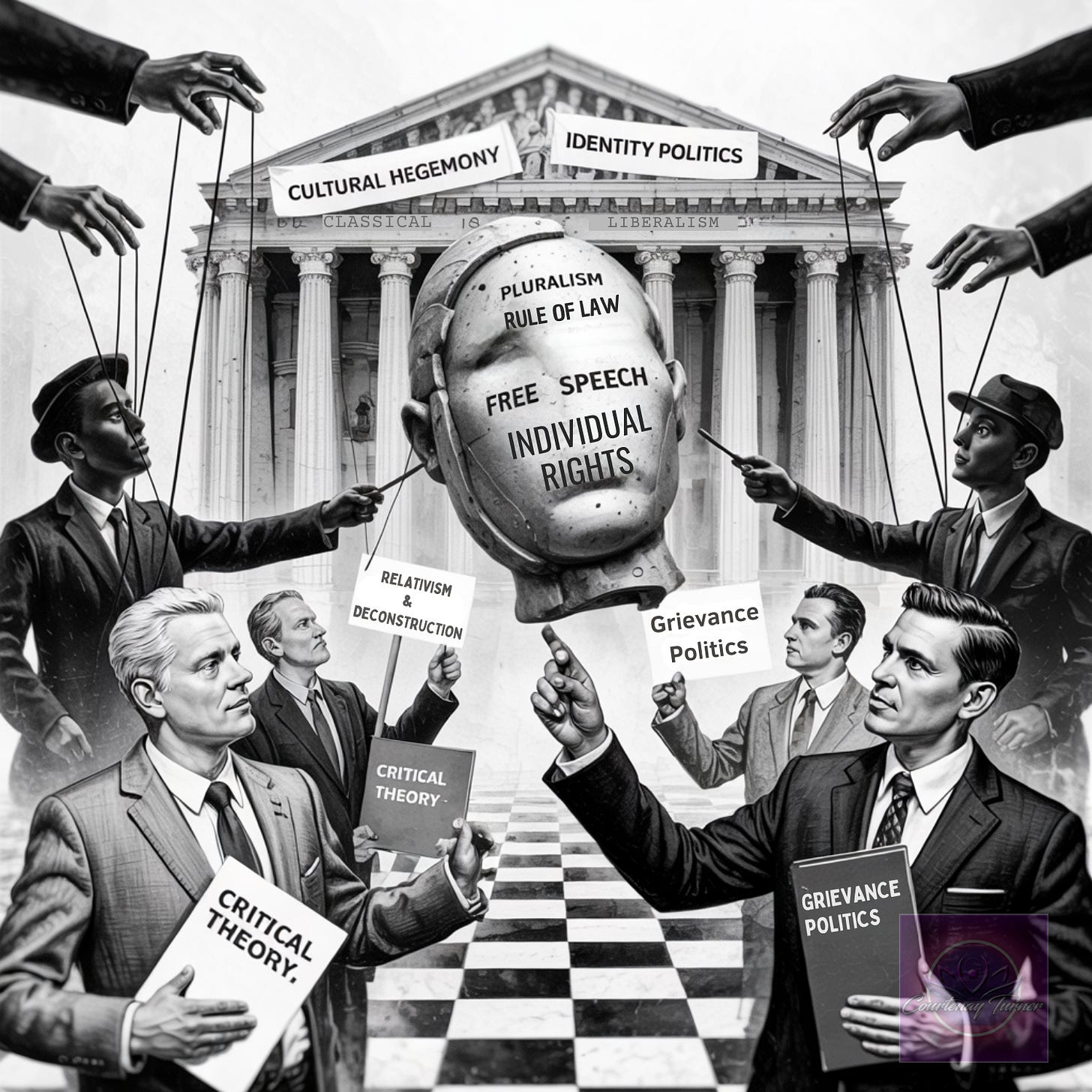

The New Right’s appropriation of Gramscian and Frankfurt School tactics in America’s ongoing culture war, and the existential tension this creates with the U.S. Constitution.

For those who prefer to listen to the article, the Author has recorded an audio version.

Introduction: Christopher Rufo’s Gramscian Moment

On a brisk spring morning April 17, 2025, Christopher Rufo, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and one of the most influential strategists on the American political right, took to social media with a declaration that sent ripples through the political establishment.

“The Right is learning new political tactics. We are not going to indulge the fantasies of the 'classical liberals' who forfeited all of the institutions. We're going to fight tooth and nail to recapture the regime and entrench our ideas in the public sphere. Get ready.”

For many, this was just another salvo in the ongoing culture war—a rhetorical flourish aimed at rallying the conservative base. But for those attuned to the deeper currents of intellectual history, Rufo’s words signaled something far more profound: a conscious, strategic embrace of the ideas of Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist philosopher whose theories of cultural hegemony and ideological struggle were once the exclusive property of the radical left.

Rufo’s new book, How the Regime Rules, is unabashed in its inspiration. “Gramsci, in a sense, provides the diagram of how politics works and the relationship between all of the various component parts: intellectuals, institutions, laws, culture, folklore,” he writes, positioning himself as an architect of “new right politics” modeled on Gramscian principles. “The right needs a Gramsci,” Rufo insists, “and my own ambition is to serve in a similar capacity, an architect of the new right politics.”.

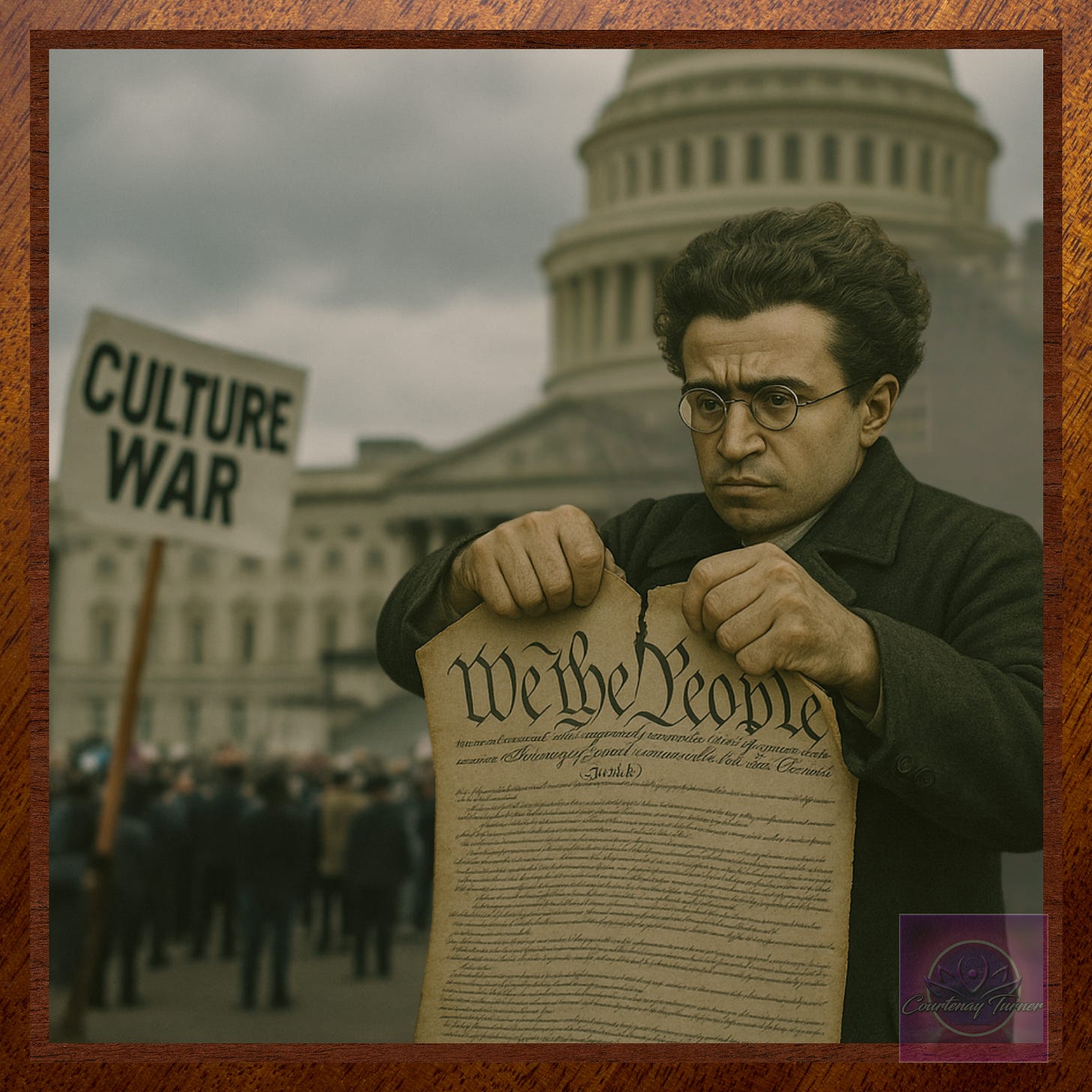

How did we get here? How did the intellectual legacy of a Marxist revolutionary become the battle plan for a movement that claims to defend the U.S. Constitution against the encroachments of socialism, progressivism, and “woke” ideology? And what does this reveal about the shifting terrain of American politics, where the boundaries between left and right, radical and conservative, are increasingly blurred?

To answer these questions, we must embark on a journey through the history of ideas—a journey that begins in the factories of early twentieth-century Turin, winds through the lecture halls of Weimar Germany, detours through the exile communities of wartime America, and arrives, unexpectedly, in the heart of today’s conservative movement.

At the center of this story is Antonio Gramsci, a man whose life was shaped by poverty, illness, and political persecution, but whose writings have exerted a gravitational pull on generations of activists and intellectuals. Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony—his insight that power is maintained not just through coercion but through the subtle shaping of beliefs, values, and common sense—has become a touchstone for those seeking to understand how societies change, and how revolutions, are won or lost.

Gramsci was not alone. His ideas found new life in the work of the Frankfurt School, a group of German-Jewish intellectuals who fled the rise of fascism and sought to adapt Marxism to the realities of the twentieth century. The Frankfurt School’s “critical theory” shifted the focus from economic exploitation to cultural domination, from class struggle to the battle for hearts and minds. Their critique of the “culture industry,” of mass media and consumerism, and of the ways in which ideology is manufactured and maintained, has become a staple of academic and activist discourse.

For decades, these ideas were the targets of conservative ire—denounced as “cultural Marxism,” blamed for the erosion of traditional values, and held responsible for the rise of identity politics and the decline of objective truth. But as the right has found itself increasingly marginalized in the institutions—universities, media, even corporate boardrooms—a new generation of activists has begun to ask: What if Gramsci was right? What if the key to political power lies not in electoral victories or legislative majorities, but in the slow, patient work of building a counter-hegemony, of capturing the commanding heights of culture—a long march through the institutions?

This is the paradox at the heart of the New Right’s Gramscian moment: a movement that claims to defend the Constitution by adopting the tactics—and, in some cases, the worldview, integral to the operational success of those tactics—of its most determined critics. It is a development that raises profound questions about the nature of American governance, the resilience of constitutional norms, and the future of the culture war.

In the pages that follow, we will trace the intellectual genealogy of this moment, from Gramsci’s early influences to the spread of critical theory in America, from the philosophical underpinnings of the Frankfurt School to the contemporary battles over free speech, pluralism, and the rule of law. We will examine the points of conflict—and unexpected convergence—between the collectivist, revolutionary aspirations of the left and the increasingly radicalized strategies of the right. And we will ask what all of this means for the Constitution, for the idea of America, and for the possibility of a pluralistic, Constitutional republican society in an age of ideological warfare.

The New Right’s Gramscian Moment

In recent years, a striking intellectual realignment has emerged within the American right. Figures such as Christopher Rufo, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, have openly embraced the tactics and theoretical frameworks of Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Communist philosopher once regarded as a nemesis of Western conservatism. Rufo’s declaration—“The Right is learning new political tactics. We are not going to indulge the fantasies of the 'classical liberals' who forfeited all of the institutions. We're going to fight tooth and nail to recapture the regime and entrench our ideas in the public sphere. Get ready.”—signals a strategic pivot away from the classical liberalism that underpinned much of 20th-century American conservatism.

Rufo’s new book, How the Regime Rules, is described as a “manifesto for the New Right,” explicitly drawing inspiration from Gramsci’s analysis of how political power is exercised through a complex interplay of intellectuals, institutions, laws, culture, and folklore. This is not an isolated phenomenon: a growing faction on the right believes that the left’s success over the past half-century can be traced to its adoption of Gramscian tactics—namely, the “long march through the institutions” and the strategic use of cultural power to shift the Overton window and redefine consensus.

This approach marks a break with the right’s traditional suspicion of radical theory and its historic defense of classical liberal principles—individual liberty, limited government, and pluralism. Instead, the New Right now seeks to use the tools of cultural and institutional power, sometimes even advocating illiberal tactics, to achieve conservative ends. The irony is not lost on critics: Gramsci was a doctrinaire Marxist, loyal to the Communist Party and Moscow, whose theories were crafted to overthrow the very liberal order the right once championed. Yet, as Rufo and his allies argue, the battle for cultural dominance is now so central that even the methods of a “favorite communist” are worth repurposing if they offer a blueprint for victory.

Antonio Gramsci: Life, Thought, and Revolutionary Praxis

Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) was not a conventional academic but a radical journalist, political activist, and eventually the leader of the Italian Communist Party. Born in Sardinia to a poor family, Gramsci’s early experiences of poverty and marginalization shaped his sensitivity to issues of inequality and cultural domination. His intellectual journey began in Turin, where he was exposed to industrial radicalism, factory councils, and the vibrant debates of the Italian Socialist Party.

Gramsci’s political activism was marked by his commitment to revolution and his deep engagement with the immediate political crises of interwar Italy—particularly the rise of fascism and the failures of the left to build a united front. His most influential writings, the Prison Notebooks, were composed during his incarceration by Mussolini’s regime from 1926 until his death in 1937. In these notebooks, Gramsci developed a nuanced theory of power that broke with classical Marxist economic determinism. He argued that in advanced capitalist societies, the ruling class maintains dominance not simply through coercion or control of the means of production, but through “hegemony”—a process of intellectual and moral leadership that permeates civil society through culture, education, religion, and media.

Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony was revolutionary: it explained why capitalist societies could survive crises that, according to orthodox Marxism, should have led to their collapse. He insisted that the superstructure—culture, ideology, and institutions—was as vital as the economic base in shaping society. Gramsci also emphasized the role of “organic intellectuals,” individuals who emerge from and articulate the interests of specific social classes, as agents of ideological transformation. His “war of position” called for a long-term, strategic struggle for cultural dominance, in contrast to the direct, insurrectionary “war of maneuver” favored by earlier revolutionaries.

Gramsci’s legacy is thus one of intellectual innovation and strategic adaptation—a Marxism that recognized the centrality of culture, identity, and ideas in the struggle for power. His theories have had a profound impact not only on the left but, as recent developments show, on the right as well.

The Intellectual Genealogy: Influences on Gramsci

Gramsci’s thought was shaped by a rich tapestry of intellectual, political, and cultural influences, which he synthesized into a distinctive Marxist theory of cultural and political power.

Marx and Engels:

Gramsci’s foundational framework was Marxism, especially the theories of class struggle, historical materialism, and the role of ideology in capitalist societies. He drew on Marx’s The Communist Manifesto and Das Capital to analyze economic exploitation and class power, but he expanded Marx’s focus on economics by emphasizing the importance of culture and ideology in maintaining capitalist dominance.

Vladimir Lenin:

Lenin’s revolutionary strategy and emphasis on the disciplined vanguard party deeply influenced Gramsci’s early activism. Gramsci met Lenin in Moscow in the early 1920s, and while he adopted Lenin’s focus on political leadership, he diverged by stressing the need for a broader, cultural approach to revolution. Gramsci’s “war of position” was a response to Lenin’s “war of maneuver,” reflecting his belief that Western societies required a slower, more strategic cultural struggle due to their entrenched civil institutions.

Hegel and Italian Idealism (Benedetto Croce, Giovanni Gentile)

Through engagement with Italian Hegelian philosophers, Gramsci absorbed the dialectical method and the idea of history as a process driven by contradictions. Croce’s focus on culture, ethics, and the role of ideas in shaping society left a lasting imprint, as did Gentile’s emphasis on consciousness and education (despite Gentile’s later association with fascism). Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony can be seen as a Marxist reworking of Croce’s idea that ethical and cultural values shape societal development.

Hegel’s Dialectic, a Gnostic Jacob’s Ladder & the Machinery of Control:

Courtenay Turner Mar 11 Read full story

Antonio Labriola:

Labriola introduced Gramsci to a non-deterministic interpretation of Marxism, emphasizing the interplay of economic and cultural factors and rejecting rigid economic determinism. This informed Gramsci’s focus on the active role of culture and intellectuals in history.

Georges Sorel:

Sorel’s ideas on revolutionary myth and collective action influenced Gramsci’s understanding of how myths (such as the general strike) could mobilize the working class. Gramsci was drawn to Sorel’s emphasis on will and action but critiqued his reliance on spontaneity, opting instead for disciplined cultural and political struggle.

Niccolò Machiavelli:

Gramsci admired Machiavelli’s The Prince for its realistic analysis of power and leadership. He likened the Communist Party to Machiavelli’s “Prince,” envisioning it as a collective leader capable of unifying and mobilizing the working class. His concept of the “Modern Prince” reflects this influence.

Italian Political and Cultural Context:

Gramsci’s experiences in Turin’s factory councils, his Sardinian background, and his engagement with the Italian Socialist Party all shaped his sensitivity to issues of inequality, regionalism, and the need for grassroots organization.

Other Influences:

Russian revolutionaries like Trotsky and Kollontai influenced his views on revolutionary strategy.

Literary figures such as Dante and Manzoni shaped his interest in national culture and language.

Sociological and positivist thinkers contributed to his analysis of civil society.

Synthesis:

Gramsci synthesized these diverse influences into a framework that prioritized culture, ideology, and intellectual leadership in the revolutionary process. His engagement with Hegel, Machiavelli, and Sorel added strategic depth, while his critique of both idealism and economic determinism set him apart from orthodox Marxism. This intellectual genealogy underpins the enduring relevance—and current appropriation—of Gramsci’s ideas across the political spectrum.

Cultural Hegemony: Gramsci’s Core Concept

Antonio Gramsci’s most influential contribution to political theory is the concept of cultural hegemony. This idea, developed in the bleak solitude of Mussolini’s prisons, fundamentally reoriented Marxist thought and has reverberated across disciplines and ideologies for nearly a century.

What is Cultural Hegemony?

For Gramsci, power in modern societies is not maintained solely through force or economic control. Instead, the ruling class achieves dominance by shaping the cultural, intellectual, and moral “common sense” of society. This process, which Gramsci called hegemony, means that the values, beliefs, and norms of the dominant group become so widely accepted that they appear natural and inevitable—even to those who are disadvantaged by them.

Unlike classical Marxists, who saw the “superstructure” (culture, ideology, institutions) as a mere reflection of the economic “base” (relations of production), Gramsci argued that the superstructure was itself a crucial battleground. The state, in his view, was only one part of the equation; the real contest for power took place in civil society—the schools, churches, newspapers, voluntary associations, and even folklore that shape people’s worldviews—the long march through the institutions.

Organic Intellectuals and the Historic Bloc

Gramsci introduced the concept of organic intellectuals—individuals who emerge from and articulate the interests of a particular social class. Unlike “traditional intellectuals,” who see themselves as detached from class struggle, organic intellectuals are embedded in daily life and play a pivotal role in spreading new ideas, organizing communities, and challenging the status quo.

He also coined the term historic bloc to describe a coalition of social forces united by a shared worldview. To achieve hegemony, a class must build such a bloc, aligning its interests with those of other groups and creating a new “common sense” that can command broad consent.

War of Position vs. War of Maneuver

Gramsci distinguished between two forms of struggle:

War of Maneuver: Direct, frontal assault on state power (as in the Russian Revolution).

War of Position: A protracted, indirect campaign to win hearts and minds, gradually undermining the legitimacy of the existing order.

In Western democracies, with their entrenched civil institutions, Gramsci argued that a war of position was essential. Revolution would come not through sudden insurrection, but through the slow, patient work of cultural transformation.

Examples and Legacy

Gramsci’s theory explains why revolutions fail in societies where the ruling class has secured broad cultural consent, and why social change often begins with shifts in language, education, and media. It also highlights the importance of alliances, compromise, and the creation of new narratives.

Today, “hegemony” is a staple of academic and activist discourse, invoked to analyze everything from media bias to the persistence of systemic racism and the rise of populist movements. Gramsci’s insights have been adopted, adapted, and contested by thinkers across the political spectrum.

The Frankfurt School: From Marx to Critical Theory

While Gramsci was developing his theories in Italy, a group of German intellectuals—later known as the Frankfurt School—were grappling with similar questions about power, culture, and the failure of revolution in the West. Their work would become known as critical theory, and it would profoundly shape the intellectual landscape of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Origins and Key Figures

The Frankfurt School emerged from the Institute for Social Research, founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt. Its core members included Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, Walter Benjamin, Erich Fromm, and later Jürgen Habermas. Many were Jewish intellectuals who fled Germany after the Nazi rise to power, relocating to the United States.

From Economic to Cultural Critique

Like Gramsci, the Frankfurt School began with orthodox Marxism but soon recognized its limitations. The anticipated proletarian revolutions had not materialized in the West; instead, fascism and consumer capitalism had triumphed. Why?

Their answer lay in the power of culture. Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944) introduced the concept of the culture industry: mass media and entertainment, they argued, had become tools for manufacturing consent, pacifying dissent, and reinforcing the status quo. Popular culture was not a site of liberation but a means of social control.

Critical Theory’s Core Ideas

Instrumental Reason: The critique of Enlightenment rationality as a tool for domination, not emancipation.

Repressive Tolerance (Marcuse): The idea that liberal societies use tolerance selectively, allowing harmful or oppressive ideas to flourish while marginalizing genuine dissent. The notion that liberal tolerance can perpetuate oppressive systems by allowing harmful ideas to flourish, necessitating selective intolerance to achieve justice. “Liberating tolerance, then, would mean intolerance against movements from the Right and toleration of movements from the Left.”

One-Dimensional Man (Marcuse): The claim that advanced industrial societies create passive, conformist citizens unable to imagine alternatives.

Negative Dialectics (Adorno): The insistence on perpetual critique and resistance to closure or dogma.

Influence on the New Left and Beyond

The Frankfurt School’s ideas migrated to the United States, where they influenced the New Left, civil rights activists, feminists, and later, critical race and gender theorists. Their work provided a vocabulary for analyzing power beyond economics—focusing on language, identity, sexuality, and the subtle mechanisms of social domination.

Critics on the right would later dub this intellectual tradition “cultural Marxism,” blaming it for the erosion of traditional values and the rise of identity politics. Yet, as we have seen, its analytic tools have proven so attractive that those on the right, such as Rufo, suggest using them to critique progressive hegemony.

Critical Theory in America: From Academia to Activism

The migration of Frankfurt School thinkers to the United States during the 1930s and 1940s set the stage for a profound transformation of American intellectual and political life. Their ideas, initially confined to academic circles, gradually seeped into mainstream culture, activism, and public policy.

Academic Influence and the New Left

After World War II, figures like Herbert Marcuse found positions at American universities, where they mentored a new generation of radical scholars and activists. Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man (1964) became a touchstone for the New Left, inspiring students to critique not only capitalism but also the conformism of mass society. The Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, the anti-Vietnam War protests, and the rise of second-wave feminism all bore the imprint of critical theory’s skepticism toward authority and its emphasis on emancipation.

Critical Theory’s Expansion: Race, Gender, and Identity

By the 1970s and 1980s, critical theory had evolved and diversified. Scholars like Angela Davis, bell hooks, and Kimberlé Crenshaw drew on its methods to analyze the intersections of race, gender, and class. Critical race theory, queer theory, and postcolonial studies all owe a debt to the Frankfurt School’s insistence that culture, language, and identity are battlegrounds for power.

From the Academy to the Public Sphere

Critical theory’s influence extended beyond the ivory tower. Concepts such as “systemic oppression,” “privilege,” and “intersectionality” entered mainstream discourse, shaping debates over affirmative action, policing, education, and media representation. Activists used critical theory to expose hidden structures of domination and to demand institutional reform.

The Conservative Backlash

As critical theory gained ground, it provoked a fierce backlash from conservatives, who saw it as an attack on traditional values, meritocracy, and objective truth. The term “cultural Marxism” became a catch-all epithet for a perceived leftist assault on Western civilization. Yet, in a twist of intellectual history, some on the right began to appropriate critical theory’s tools—deconstruction, identity politics, and the critique of liberal neutrality—to wage their own war of position against progressive hegemony.

Today, critical theory is both celebrated and reviled. Its concepts are invoked in debates over everything from school curricula to corporate diversity training. Its analytic framework—power is everywhere, culture is political, emancipation requires unmasking hidden domination—remains central to the way Americans argue about justice, freedom, the future of democracy and the constitutional republic.

Gramsci and the Frankfurt School: Parallels and Divergences

Antonio Gramsci and the Frankfurt School are often grouped together under the umbrella of “cultural Marxism,” but their theories, while sharing key similarities, also diverge in important ways.

Shared Foundations and Overlapping Concerns

Both Gramsci and the Frankfurt School sought to update Marxist theory for the realities of 20th-century Western societies, where direct revolutionary action had failed and capitalism proved more resilient than orthodox Marxism predicted. They recognized that power was not exercised solely through economic control or state coercion, but also through culture, ideology, and the consent of the governed.

Cultural Hegemony and Ideology: Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony—the idea that the ruling class maintains dominance by shaping cultural norms and “common sense”—finds a parallel in the Frankfurt School’s focus on ideology and the “culture industry.” Both saw civil society (schools, churches, media, voluntary associations) as the primary battleground for social change, not merely the state or economy.

Critical Social Theory: Both traditions emphasized the need for a “counter-hegemony” or critical theory that could expose and challenge the dominant ideology, paving the way for social transformation.

Key Differences

Optimism vs. Pessimism: Gramsci retained faith in the “will” of the working class to achieve emancipation through a “war of position”—a long-term, strategic struggle for cultural dominance— a long march through the institutions. The Frankfurt School, by contrast, developed a more pessimistic outlook, seeing mass culture as a tool of pacification and doubting the revolutionary potential of the proletariat in advanced capitalist societies.

Focus of Critique: Gramsci’s analysis was rooted in the specific historical and political context of Italy, emphasizing the need to build alliances and a “historic bloc” among various social forces. The Frankfurt School, shaped by the rise of fascism in Germany and exile in America, turned its attention to the psychological and cultural mechanisms of domination, such as the “culture industry” and “repressive tolerance”.

Approach to Reason and Subjectivity: The Frankfurt School critiqued the separation of reason from objectivity and the resulting alienation, whereas Gramsci focused more on the active role of intellectuals and the unity of theory and practice.

While Gramsci’s writings directly influenced the early Frankfurt School—particularly Max Horkheimer’s definition of critical theory as a non-dogmatic, liberating social critique—their respective legacies diverged. Gramsci’s optimism about cultural struggle inspired later leftist movements and, ironically, some factions on the right, while the Frankfurt School’s skepticism about mass emancipation led to a more enduring critique of both capitalism and mass democracy.

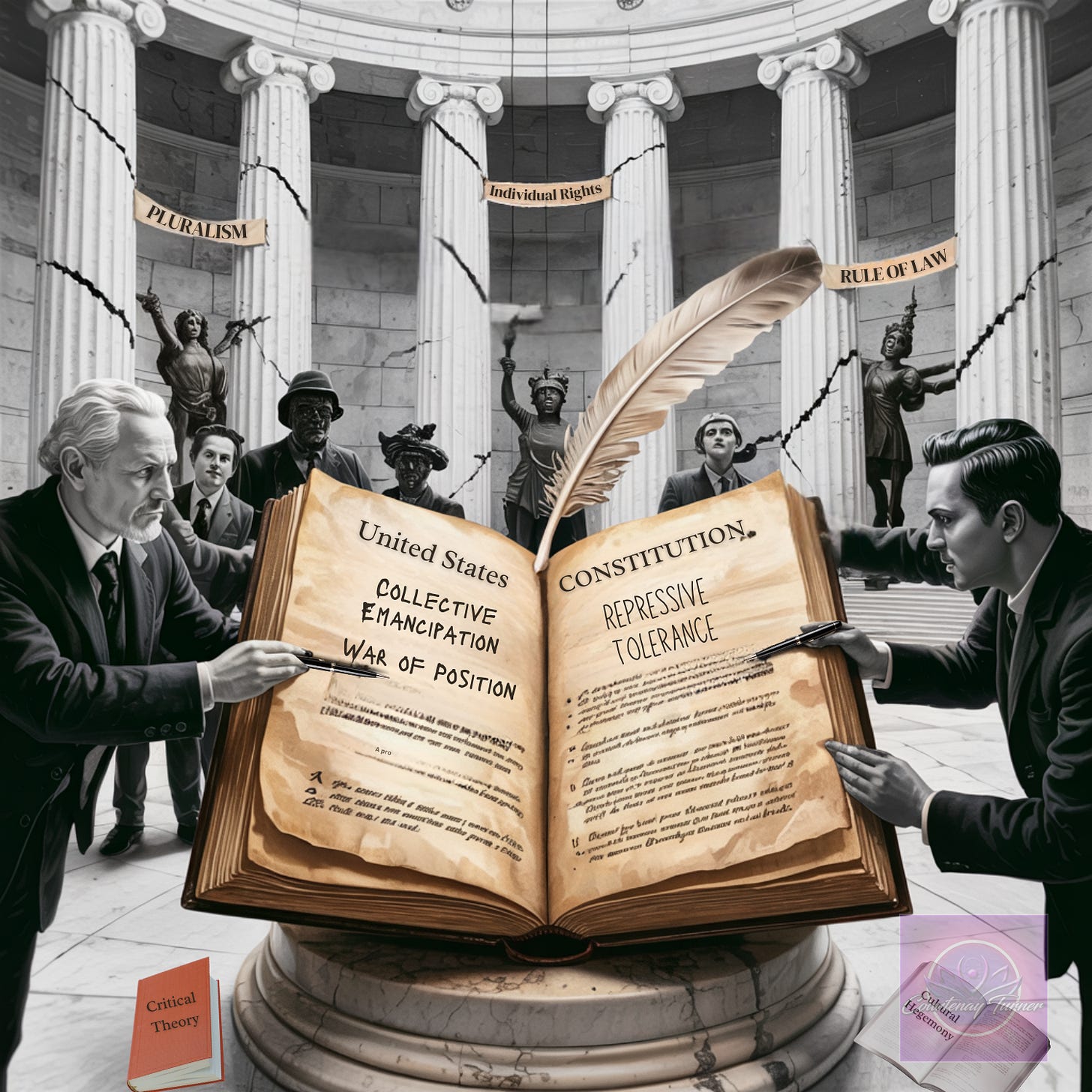

Why Gramsci and the Frankfurt School Clash with the U.S. Constitution

The core ideas of Gramsci and the Frankfurt School are fundamentally at odds with the principles enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. This conflict can be seen across several dimensions:

Gramsci/Frankfurt School vs U.S. Constitution

Collective emancipation/class struggle vs Individual rights and liberties.

Cultural dominance/ideological unity vs Pluralism, marketplace of ideas

Revolutionary change/subversion vs Stability, rule of law, incremental reform

Critique of private property/capitalism vs Protection of property, free enterprise

Group-based morality/oppression vs Equal protection, due process, legal equality

Collectivism vs. Individualism

Gramsci and the Frankfurt School prioritize collective emancipation and the transformation of society through ideological and cultural struggle. Their frameworks subordinate individual rights to the needs of the group or class, viewing individual freedoms as potentially complicit in maintaining oppressive systems. By contrast, the U.S. Constitution is rooted in Enlightenment liberalism, emphasizing individual liberty, limited government, and the protection of personal rights through mechanisms like the Bill of Rights, separation of powers, and federalism.

Cultural Hegemony vs. Pluralism

Gramsci’s “war of position” and the Frankfurt School’s critique of the “culture industry” both seek to expose and ultimately overturn the dominant cultural narratives of capitalist societies. Their end goal is to build a new consensus—effectively, a new hegemony—aligned with socialist or emancipatory values. The Constitution, however, is designed to foster a pluralistic society where diverse viewpoints compete in a “marketplace of ideas,” protected by the First Amendment’s guarantees of free speech, press, and religion.

Revolutionary Change vs. Constitutional Stability

The Frankfurt School’s call for systemic, even revolutionary, change—whether through cultural subversion or direct action—stands in stark contrast to the Constitution’s mechanisms for gradual, democratic reform. The amendment process, checks and balances, and representative government are all intended to ensure stability and continuity, not to facilitate rapid or radical transformation.

Property and Economic Freedom

Both Gramsci and the Frankfurt School are critical of private property as a source of alienation and inequality, advocating for its transformation or abolition as part of a broader socialist project. The Constitution, by contrast, explicitly protects property rights (e.g., the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause) and commerce, embedding economic freedom as a core value.

Freedom of Speech and Tolerance

Marcuse’s concept of “repressive tolerance” (that certain forms of speech should be suppressed to achieve true justice) and the Frankfurt School’s skepticism of liberal freedoms directly challenge the First Amendment’s broad protection of expression—even for unpopular or “oppressive” views. The Constitution’s approach is to protect dissent and diversity of opinion as essential to liberty.

The Woke Right

According to Kevin Deyoung in his article The Rise of Right-Wing Wokeism,

“When Wolfe sarcastically thanks those who ‘woke many from their dogmatic slum- ber’ and rejoices that ‘more are awakening each day,’ one might be forgiven for seeing his version of Christian Nationalism as a form of right-wing wokeism. What does it mean to be woke if not that we’re awakened to the ‘reality’ that oppression is everywhere, extreme measures are necessary, and the regime must be overthrown?

If critical race theory teaches that America has failed, that the existing order is irre- deemable, that Western liberalism was a mistake from the beginning, that the cur- rent system is rigged against our tribe, and that we ought to make ethnic conscious- ness more important—it seems to me that Wolfe’s project is the right-wing version of these same impulses.”

The term “woke right” (see Courtenay Turner’s substack article) refers to a segment of right-wing political and cultural actors who adopt rhetorical strategies, analytical frameworks, or ideological tactics that resemble those traditionally associated with left-leaning “woke” movements, such as identity politics, grievance culture, or deconstructive critiques of societal norms. While the woke right is not a monolithic group, it employs elements of critical theory, postmodernism, and poststructuralism—intellectual frameworks historically tied to leftist scholarship, including the Frankfurt School and thinkers like Antonio Gramsci—to advance conservative or reactionary agendas. “Wokeism” is best thought of as an operating system. The woke right’s adoption of critical theory, postmodernism, and poststructuralism is a selective, strategic appropriation of their methods and rhetoric. This is often done to critique perceived liberal hegemony, reframe conservative grievances, or destabilize mainstream narratives. To learn more about the philosophical underpinnings of the “Woke Right” see my x thread (in 6 parts here)

The Woke Right: How the Radical Left’s Playbook Became the Right’s Secret Weapon

Courtenay Turner Apr 22 Read full story

The “Woke Right”: Strategic Mimicry and Its Contradictions

In a striking twist, some factions of the American right—dubbed the “woke right”—have begun to appropriate the very tools of critical theory, postmodernism, and poststructuralism that originated with the left and the Frankfurt School, deploying them for conservative or reactionary ends. “Wokeism” is best thought of as an operating system. The woke right’s adoption of critical theory, postmodernism, and poststructuralism is a selective, strategic appropriation of their methods and rhetoric. This is often done to critique perceived liberal hegemony, reframe conservative grievances, or destabilize mainstream narratives.

Strategic Mimicry of Leftist Frameworks

Critical Theory: The woke right uses the methods of ideology critique to deconstruct what they see as liberal or progressive cultural dominance in institutions like media, academia, and government. This mirrors Gramsci’s “war of position,” but the target is now progressive elites rather than capitalist ones.

Postmodernism and Poststructuralism: By adopting postmodern skepticism of objective truth, the woke right challenges liberal narratives about history, science, and morality, reframing debates in terms of cultural construction and power relations.

Identity Politics and Grievance Culture: The woke right flips the Frankfurt School’s focus on marginalized groups, portraying conservatives, Christians, or white Americans as the new oppressed classes. This is used to justify calls for a conservative counter-hegemony, echoing the left’s use of identity politics for social change.

Contradictions and Constitutional Tensions

While these tactics have proven effective in mobilizing conservative constituencies and challenging liberal dominance, they create significant philosophical and practical contradictions:

Incoherence with Traditional Conservatism: Traditional conservatism values order, objective truth, and respect for established institutions—principles at odds with postmodern relativism and the revolutionary ethos of critical theory.

Threats to Constitutional Principles: The woke right’s use of deconstruction, censorship, and group-based grievance politics can undermine the very constitutional principles they claim to defend—such as free speech, pluralism, and equal protection under the law.

Risk of Illiberalism: By seeking to impose their own cultural hegemony and restrict dissenting views, the woke right risks replicating the very forms of ideological dominance and intolerance they criticize in the left, threatening the pluralistic foundation of the American constitutional order.

The woke right often cherry-picks these frameworks’ rhetorical tools (e.g., deconstruction, grievance). Traditional conservatism, and proponents of constitutional preservation/ restoration, values order, tradition, and objective truth, which clash with postmodernism’s relativism and critical theory’s revolutionary ethos. They rewrite history or challenge narratives, often with ethnocentric or anti-Semitic undertones. Woke right adapts postmodern and critical theory tactics to push a “Critical Social Justice” framework for “conservative” ends.

The woke right selectively uses critical theory, postmodernism, and poststructuralism to deconstruct liberal cultural dominance, reframe conservative grievances, and control discourse, mirroring tactics pioneered by Gramsci and the Frankfurt School but redirecting them toward nationalist, traditionalist, or anti-progressive goals. By adopting deconstruction, relativism, and identity politics, they challenge perceived liberal hegemony clashing with the U.S. Constitution’s emphasis on individual rights, pluralism, and objective legal principles. This strategic mimicry reflects a broader cultural shift where academic theories are repurposed for political ends.

The adoption of Gramscian, Frankfurt School, and Marxist strategies by dialectical poles, in America’s culture wars reveals a deep and ongoing tension between the drive for collective transformation and the constitutional commitment to individual liberty, pluralism, and the rule of law. As dialectical tensions vie for cultural dominance, the resilience of the Constitution—and the future of the American republic—hangs in the balance.

The Rhetoric of Grievance and Identity

The New Right has embraced grievance politics, reframing conservatives, Christians, and white Americans as marginalized groups under siege by an ascendant progressive elite. This mirrors the Frankfurt School’s analysis of alienation and the left’s use of identity politics, but inverts the direction of victimhood. The result is a potent narrative that mobilizes supporters and justifies aggressive tactics.

Conclusion: The Future of the Culture War and American Constitutionalism

The New Right’s adoption of Gramsci, the Frankfurt School, Marxists and Alinsky’s playbook marks a profound shift in American political strategy. What began as a leftist project to subvert capitalist hegemony has been appropriated by conservatives seeking to reclaim institutions and entrench their own vision of American identity. This ideological cross-pollination has intensified the culture war, attempting to foist a color revolution, raising fundamental questions about the future of the constitutional republic.

The Stakes: Pluralism vs. Hegemony

At its core, the struggle is over whether American society will remain pluralistic—committed to the constitutional principles of free speech, individual rights, and incremental change—or whether it will succumb to the logic of cultural hegemony, where one side seeks to dominate the institutions—operational success of the long march through the institutions— and define the national narrative. Both left and right now deploy strategies aimed at capturing the “commanding heights” of culture, often at the expense of constitutional principles and laws.

Risks to Constitutional Order

The Gramscian approach, when wielded by either camp, tends to erode the very foundations of the U.S. Constitution:

Erosion of Free Speech: Both sides have supported restrictions on speech they deem harmful, undermining the First Amendment’s protections.

Undermining Pluralism: The pursuit of cultural dominance risks suppressing dissent and narrowing the range of acceptable viewpoints, contrary to the pluralist spirit of the Constitution.

Destabilizing Rule of Law: Efforts to bypass legislative deliberation in favor of executive or judicial fiat, or to use state power to enforce ideological conformity, threaten the stability and legitimacy of constitutional governance.

The constitutional system was designed to mediate conflict through reasoned discourse, and respect for individual rights. The culture war’s transformation into a zero-sum contest for hegemony undermines these mechanisms, making representative self-government more difficult.

Recommitting to the constitutional framework is essential if America is to weather this period of polarization and preserve its experiment in self-governance as a Constitutional Republic.

What Is at Stake: Can the Constitution Survive the New Culture War?

The appropriation of Gramscian and Frankfurt School tactics by the New Right is a testament to the enduring power of ideas—but it is also a warning. When all sides of the political spectrum seek to impose their vision through cultural dominance, the very fabric of the constitutional republic is at risk.

Key Questions for the Future:

Can American society sustain a pluralistic order in which competing visions coexist, or will the pursuasiveness of cultural hegemony triumph, leading to dialectical cycles of domination and backlash?

Will the Constitution’s protections for free speech, due process, and individual liberty prove resilient enough to withstand assaults from the dialectical left and right, or will they be eroded by the teleological drive for power and control forcing ideological conformity?

Can Americans rediscover the art of reasoned disagreement and representative democratic deliberation, or will the culture war continue to escalate fomenting a color revolution, undermining the possibility of self-government?

As the culture war rages on, the challenge is to resist the temptation to fight fire with fire—to avoid becoming what one opposes. The Constitution’s genius lies in its commitment to pluralism, process, and the dignity of the individual. Preserving these principles is the only way to ensure that the American experiment endures, even as the battle for the soul of the nation continues. “It’s a Republic if you can keep it.” This means we must avert forces attempting to “Phoenix it”. (see Courtenay’s podcasts for a deeper explanation of the term.)

A Republic If You Can "Phoenix It", Game B?

Courtenay Turner October 22, 2024 Read full story

The New Right’s Gramscian turn is but fraught with long-term risks for the constitution. Whether the United States can navigate this moment without sacrificing its foundational commitments to liberty, pluralism, and the rule of law remains the central question of our time.

Upon reviewing Rufo’s conversation with Jonah Goldberg perhaps it’s worth considering Alinsky dedicated his book Rules For Radicals to the “very first radical”, Lucifer,

“Lest we forget at least an over the shoulder acknowledgment to the very first radical: from all our legends, mythology and history (and who is to know where mythology leaves off and history begins - or which is which), the very first radical known to man who rebelled against the establishment and did it so effectively that he at least won his own kingdom - Lucifer.”

- Saul Alinsky Rules For Radicals

It’s my hope that “Conservatives” will reflect upon what it is they are trying to “conserve”. When pondering the implementation of Alinsky, Gramci, or Cultural Marxist tactics in the hopes of short term operational success, it would behoove us to weigh if the ends justify the means— or do the means potentially eviscerate the Constitution and founding principles of the United States? The New Right’s Gramscian turn is fraught with long-term risks for the constitution. Whether the United States can navigate this moment without sacrificing its foundational commitments to liberty, pluralism, and the rule of law remains a defining issue of our era.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. (Referenced in discussions of the culture industry and Frankfurt School core concepts.)

Alinsky, Saul D. Rules for Radicals. (Quoted regarding radicalism and cultural subversion.)

Benjamin, Walter. Selected Writings. (Frankfurt School member; referenced for contributions to critical theory.)

Croce, Benedetto. “Benedetto Croce.” Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedetto_Croce(Cited as a major influence on Gramsci’s philosophy.)

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. (Referenced in discussions of poststructuralism and deconstruction.)

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. (Referenced in analysis of poststructuralism and power-knowledge.)

Gentile, Giovanni. “Giovanni Gentile.” Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Gentile(Referenced as an influence on Gramsci’s views on education and idealism.)

Gramsci, Antonio. Prison Notebooks. (Referenced throughout for concepts such as cultural hegemony, organic intellectuals, and war of position.)

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. The Phenomenology of Spirit. (Cited as a philosophical influence on Gramsci via Croce and Italian idealism.)

Horkheimer, Max. Critical Theory: Selected Essays. (Frankfurt School founder; referenced for the development of critical theory.)

Labriola, Antonio. “Essays on the Materialist Conception of History.” https://www.marxists.org/archive/labriola/index.htm (Cited for non-deterministic Marxism and influence on Gramsci.)

Lenin, Vladimir. What Is to Be Done?https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/download/what-itd.pdf (Referenced as a key influence on Gramsci’s revolutionary strategy.)

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. (Referenced in discussion of postmodernism.)

Marcuse, Herbert. One-Dimensional Man. (Referenced for the Frankfurt School’s impact on the New Left and the concept of repressive tolerance.)

Machiavelli, Niccolò. The Prince. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/machiavelli/ (Referenced for Gramsci’s concept of the “Modern Prince.”)

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf (Foundational Marxist text shaping Gramsci’s framework.)

Matthews, Timothy. “The Frankfurt School: Conspiracy to Corrupt.” (Cited for analysis of the Frankfurt School’s aims and methods.)

Rufo, Christopher. “The Right is learning new political tactics…” X/Twitter, April 2025. https://x.com/realchrisrufo/status/1912900662821851462 (Referenced for direct statements on Gramsci’s influence on the New Right.)

Sorel, Georges. “Georges Sorel.” Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Sorel and Reflections on Violence. (Cited for the concept of revolutionary myth and collective will in Gramsci’s thought.)

Additional sources referenced in the files:

“Frankfurt School Influence in the United States.” (Referenced for the School’s impact on American academia, activism, and critical theory.)

“Woke Right” and Critical Theory/Postmodernism. (Referenced for analysis of the appropriation of leftist frameworks by the New Right and related constitutional tensions.)

This article is a Paid Subscriber post from the Courtenay Turner Substack and is part of an multi-article series. Courtenay has generously offered our audience a chance at some of her deeper works for free. Please consider subscribing to her Substack.

You can find part 1 here and part 2 here.

Courtenay Turner is the host of the The Courtenay Turner Podcast. You can find her works at http://CourtenayTurner.com

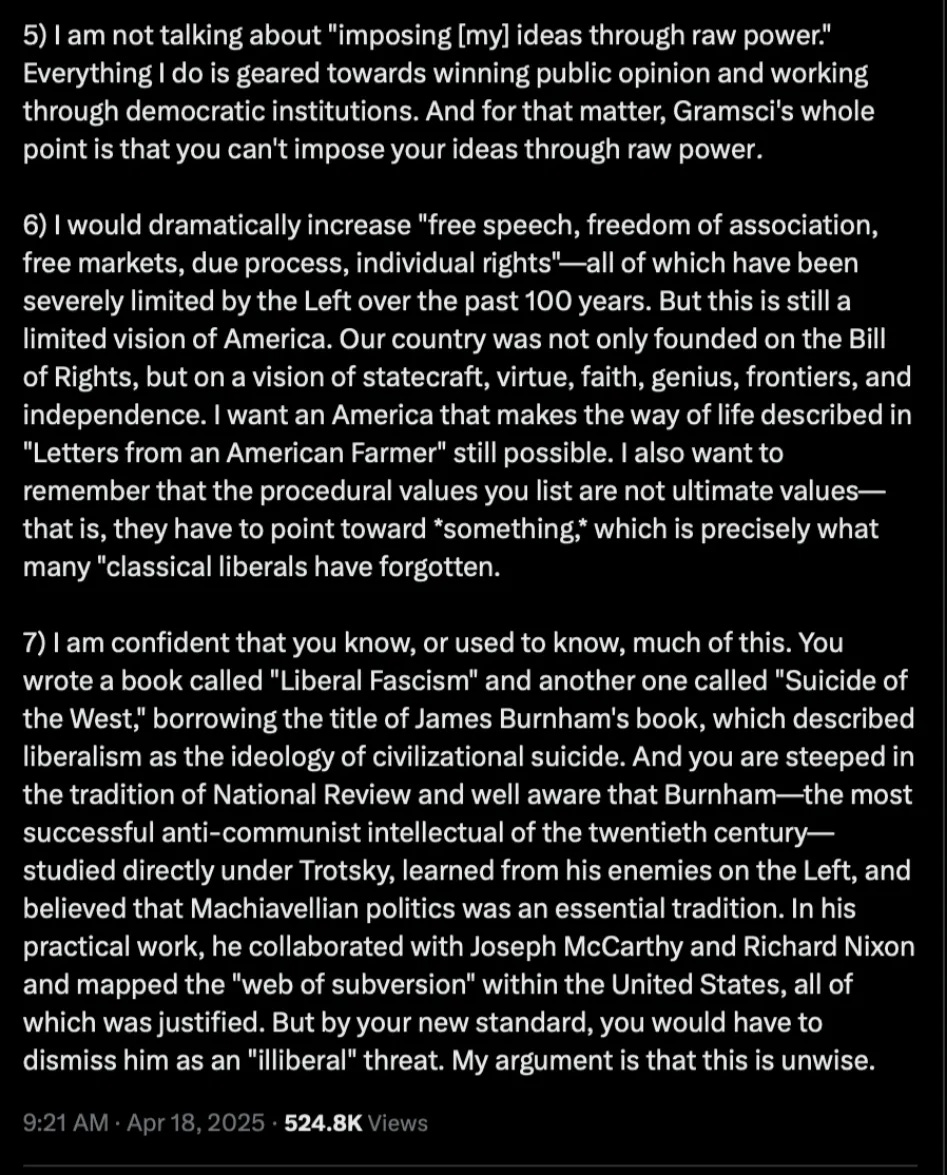

I appreciate you do quote Rufo.

Ignore for the moment his use of "Gramsci". In his long quoted post, he says that he wants to persuade the people, not use raw power. That sounds like something who honors the representative republic would do. In other words, it sounds like his entire post is "using power for good isn't evil". Rufo isn't woke, he doesn't appear to believe in any of his writings that good/evil are just social constructions but he appears to believe in consequential reality. So he appears to be saying: "Let's look at reality, determine what is good, convince the people that this is good, and if they elect us, use power to get it done." Now, I could be wrong in this interpretation. But if correct, this sounds like entirely inline with the US constitution.

Let me digress for a moment: The US constitution is not the highest good; it is a legal document. Let's talk about epistemology and ethics: I believe in a real reality that is consequential and knowable. That may sound trite, but it is the cornerstone against Woke. The woke do not believe in a real realty or if they do, it isn't knowable. The defining feature of the woke is this "constructed reality". You never demonstrated Rufo believes in this constructed reality. The progressive left tends to be made up of social constructivists, people who believe this "constructed reality" is socially defined.

Let's talk about the Woke Right: I've witness two different types of Woke on the right: (1) conservatives who want some aspect of the past, a Return. (2) a certain type of Christian constructivists. Before we go further, let's talk about the racists and antisemitism that I've see on the right (all of which I personally disavow and disagree with). There are some people who are constructivist on the right who are also racists and hold antisemitic views. But there are also some who do believe in a consequential knowable consequential reality and they believe (wrongly) that black people can't govern themselves and that (wrongly) Jews are pulling all the strings. They are not woke. They are not constructivists. They have a bad model of reality.

Let's go back to the Woke right "Return". These are often constructionists and thus "woke" because rather then holding to an ideal or consequential reality, they look to the past and say "that was better". This almost definitive what many conservatives are: look to the past and believe "that was better". They are not anchored in reality and in practice they are moored to a social phenomena rather then taking one step further, looking at the reason within reality as to why it was better or worse, and then seeking to apply those principles to the present to move the future. The other common constructivist on the right are those who's epistemology is presupisitional scripturalism. This view is common in US Christians and explicitly disavows the concept that "truth is what corresponds with reality", rather they believe truth is what exists in the mind of God ("Scripturalism: A Christian Worldview", The Trinity Review, Crampton). I call this divine constructivism.

So if Woke is to mean some form of constructivist world view, you have presented no evidence that Rufo is Woke. All direct sources appear to state the opposite that Rufo wants to shape culture to a real reality, so we can live in that reality better. To be fair, I'm also forming that view from his interviews and actions I've seen around New College FL, where he and a new board got power over the college, established a new direction that follows truth and reality. This is not what a constructivist would do.

Your argument essentially says "Gramsci" is bad, anyone who upholds part of his analysis is also bad. In otherwords, Hitler drank water, you drank water, you're bad. This is a bad form of reasoning. Yes, when you explicitly use the enemies tools, you should be very careful. But in WWII I don't think anyone was saying German engineering was inferior; we were saying your actions and ideology must be stopped. Right or wrong, I think what Rufo is saying is "What the left is doing works, it impacts the real consequential reality, where as conservatives have been routed from all levers of power and consequence. Why?" Rufo isn't saying the left's view of the world is acceptable, Rufo isn't saying anything to indicate a constructivist mind set. He is asking "Why is this effective?" Which is exactly what someone who believes in a true, knowable, consequential reality should be asking.

Eat Arby's.